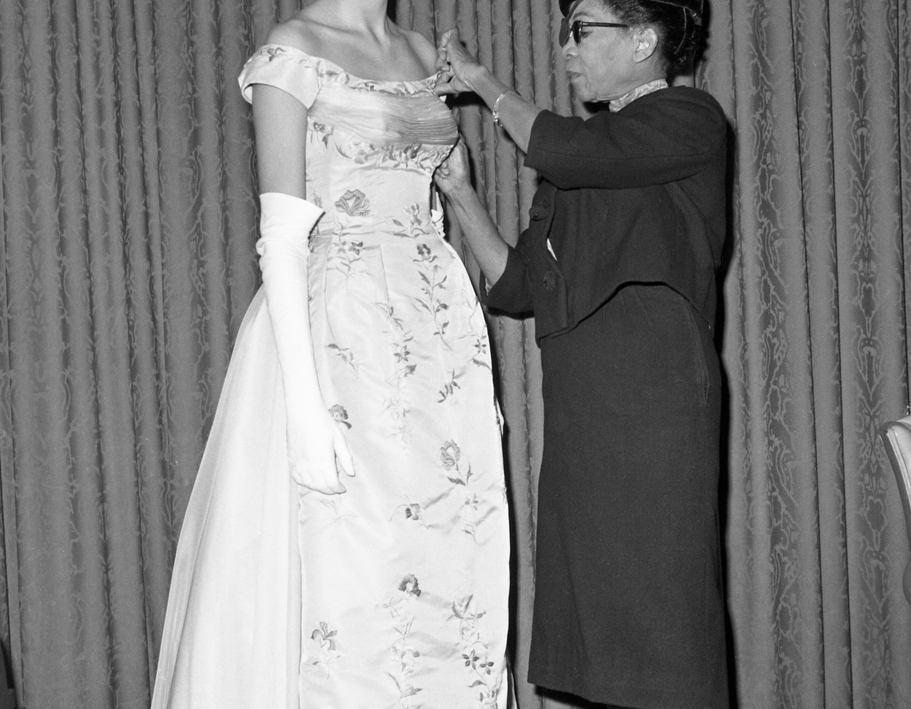

The ivory silk taffeta cascading down Jacqueline Bouvier’s frame on her wedding day wasn’t just fabric—it was a silent rebellion stitched by a Black woman the world refused to see. Ann Lowe, the ghostwriter of Jackie Kennedy’s fairy tale, sewed legacies into seams while society erased her name.

Born in Alabama clay, Lowe’s fingers learned dance from generations of women who tailored opulence for white mistresses. Her grandmother’s hands, once calloused by slavery, passed down an alchemy—transforming scraps into garden-worthy blossoms. At sixteen, when death left four unfinished ballgowns for Alabama’s first lady, Ann completed them with the precision of a prodigy. The whispers began: "There’s a girl who can make silk confess secrets."

New York’s elite collected her like forbidden art. Rockefellers and Roosevelts wore her creations, never admitting their "secret" was a Black woman working from a Harlem atelier. Lowe’s currency? Access, not profit. She undercharged dynasties, trading dollars for proximity to power—a gamble that would haunt her.

When the Bouviers commissioned Jackie’s dress, Lowe faced a gorgon’s knot: Joseph Kennedy’s meddling, a bride’s stifled Parisian dreams, and a studio flood that drowned 10 dresses days before the wedding. What followed was sartorial sorcery—50 yards of silk resurrected in five sleepless nights, while the designer swallowed $2,000 in losses (and her pride).

Blind and bankrupt, Lowe died as she lived—in fashion’s shadows. Her signature floral confections fell from vogue, but the real crime was simpler: America preferred its geniuses invisible. Today, her stitches still hold—every thread a question: Who gets remembered, and who does the remembering?